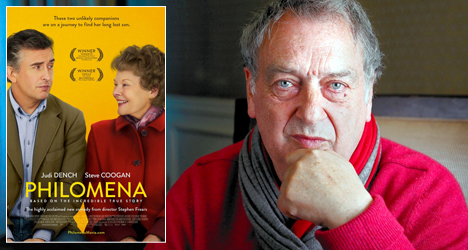

In the critically-acclaimed 2013 drama “Philomena,” two-time Oscar-nominated director Stephen Frears (“The Grifters,” “The Queen”) tells the true-to-life story of Philomena Lee, a young Irish teenager forced to give her child up for adoption while under the care of a Catholic Church convent. Fifty years later, Philomena (Judi Dench) turns to British reporter Martin Sixsmith (Steve Coogan) and asks him to help her locate her son and tell her incredible story. The result was Sixsmith’s 2009 book “The Lost Child of Philomena Lee,” which was adapted into an Oscar-nominated script by Coogan and screenwriter Jeff Pope.

During an interview with Frears, 72, we talked about how little directing he actually had to do when working with Dame Dench, his thoughts on taking creative license with a film like “Philomena” and touched a bit on his next project, an untitled film on disgraced American cyclist Lance Armstrong.

“Philomena” is available on DVD/Blu-ray April 15, 2014.

Judi Dench has stated in past interviews how much responsibility she felt to the real Philomena Lee in telling her story. Do you feel the same as a director when you take on a true-to-life project like this?

Yes, of course. I mean, it’s not the heaviest burden in the world, but yes. I don’t think you could make a film about a real person and not take on that responsibility.

How was telling her story different than, say, capturing a real person like Queen Elizabeth in “The Queen?” Do you handle the storytelling aspects in the same way?

I would imagine so. “The Queen” was slightly different because everybody knows how the story ends. You haven’t got that trick up your sleeve. You’re just telling a story.

You’ve worked with Judy before and with other amazing actresses in your career like Helen Mirren and Anjelica Huston. How much directing do you have to do with women of this caliber? Is more about standing back and watching them work?

It’s more about standing back and watching them work. They are very clever women. What you’re really trying to do is create a space where they can do their very fine work.

Because Philomena Lee’s story, at times, is incredibly heartbreaking, what were your initial thoughts when you learned Steve Coogan, who is known more for his comedy, had obtained the rights to Martin Sixsmith’s book?

That’s what I liked most about it. I could see the story was tragic and comic. The comic side of it, somehow, rounded out the whole thing.

What about some of the more serious aspects of the story like the issues with the Catholic Church? Did you want the film to feel like an indictment of the practices of the Church back then?

Listen, the Catholic Church is very, very easy to criticize. What I was more interested in was [Philomena’s] devoutness and faith. What I’ve been told is that there are worse things that happen [in the Catholic Church] than what we show.

How do you feel as a director when people refer to the film as propaganda? I mean, leaders in the Catholic Church have come out to admonish the film as anti-Catholic.

Well, I’m very, very keen on the Pope seeing the film. If I was the Pope, I think I would like this film very much. It seems to be saying what the Pope has been saying. [Note: In February 2014, a Vatican spokesperson made the following statement: “The Holy Father does not see films, and will not be seeing this one. It is also important to avoid using the Pope as part of a marketing strategy.” The Pope, however, did meet Philomena Lee at the Vatican during that same week.

Speaking of Pope Francis, he’s been making a lot of interesting comments and decisions during his short tenure as pontiff. Do you feel like he’s changing the Church’s image in a positive way?

I’m not a Catholic, so I don’t know a lot about it, but he’s seems like a very good man. Well done whoever elected him. And well done him.

Well, I’m sure you know that his comments on a lot of social issues have surprised a lot of Catholics since they go against the Church’s past stances on certain things like homosexuality and atheism.

I think that’s what the film talks about about, too. We do know someone from the Vatican has, in fact, seen [“Philomena”].

Did anything come out of that?

(Laughs) I don’t know. [The Catholic Church] doesn’t tell me their secrets.

I think the Pope would be open-minded enough to embrace the film.

That’s what I think. That’s what I’d hope.

Now, in the film, you don’t reference the convent Philomena is sent to as a Magdalene Laundry, but do you consider it one? If so, are these institutions something you researched for the film?

Not being Catholic, I am still sort of vague about what [a Magdalene Laundry] describes. A lot of Catholics worked on the film and I had a lot of Irish people in it. I was surrounded by people who knew a lot more than I did.

Talk about taking artistic license and the challenge it presents when making a true-to-life film. I mean, when you, Steve and Jeff decide to create something in the story solely for cinematic purposes, is that a difficult decision to make? Or is everything in the name of good entertainment?

You just know instinctively where the line is. I knew where it was in “The Queen.” There aren’t any rules, but you just think, “Well, that makes sense” or “That’s fair.” When I was making a film about [former Prime Minister of the United Kingdom] Tony Blair (2003’s made-for-British-TV film “The Deal”), I couldn’t really show his appalling behavior over [issues with] Iraq. It just wasn’t appropriate for the film. I thought his behavior over Iraq went very, very bad. So, I was bending over backwards to show him in a reasonable light.

It must have been easier with someone like author Martin Sixsmith on your side.

He was very kind and generous, yes. It was a very complicated narrative. At times I thought, “Well, I got away with that” or “Well, I just walked through a mind field,” but I seem to have survived.

You’re next film, of course, is the Lance Armstrong biopic. This past year, the documentary “The Armstrong Lie” came out as a sort of indictment of him and his career. How are you tackling this subject? Was it difficult to do it without turning him into an antagonist?

He’s made it quite easy for people to think of him [as an antagonist]. But, of course, he is a very complicated man. This isn’t a biopic. It’s an account of about 10 years of his life.

You made your first film in 1988 with “Dangerous Liaisons.” What have you learned about yourself as a director as you’ve maneuvered your way through the Hollywood industry over the last 25 years?

I’ve become more experienced. I must’ve loved something about it. I’ve learned how easy it is to make matters worse. The film industry has gotten harder; much tougher. I can’t believe I’m still making films.

Right, you’re still making great films, so why ever retire?

Well, firstly, it’s very hard work. Secondly, I depend on finding material that catches my imagination.

So, are you saying there are fewer and fewer of those inspiring scripts coming across your desk?

Well, at the moment I’m so exhausted I haven’t read anything. I’ve been very, very lucky with the films I’ve got to make. I’ve gotten very, very good scripts written by very, very good writers. And I’ve gotten good actors on top of that. But sometimes you just think, “Well, maybe now, my luck will run out.”

Actor Dustin Hoffman is going to be in your Lance Armstrong movie. You haven’t worked with him since your 1992 film “Hero.” That must’ve been an exciting reunion on the set.

Yeah, I worked with him for a few days just before this past Christmas. He’s a wonderful fellow and actor. It was very, very generous of him. I was very, very touched.

When you go back and work with someone like him after 20 years, does it feel like you picked up where you left off?

Yes, and we are both older and wiser. (Laughs) Or perhaps older and more foolish.